When it comes to user-friendly yet powerful operating systems, macOS stands prominently among the global leaders. Originally launched by Apple in the early 1980s, macOS has evolved dramatically, shaping not just how we interact with computers, but also setting industry benchmarks for design, usability, and security. Understanding the evolution of macOS isn't just for tech enthusiasts; it's essential knowledge for anyone using or considering Apple products.

At Esmond Service Centre, we pride ourselves on being at the forefront of technology education and support. Leveraging our extensive experience in supporting Apple devices and software, this comprehensive overview will guide you from the humble beginnings of macOS to its current cutting-edge state in 2025, offering clear insights that are practical and valuable for users across all skill levels.

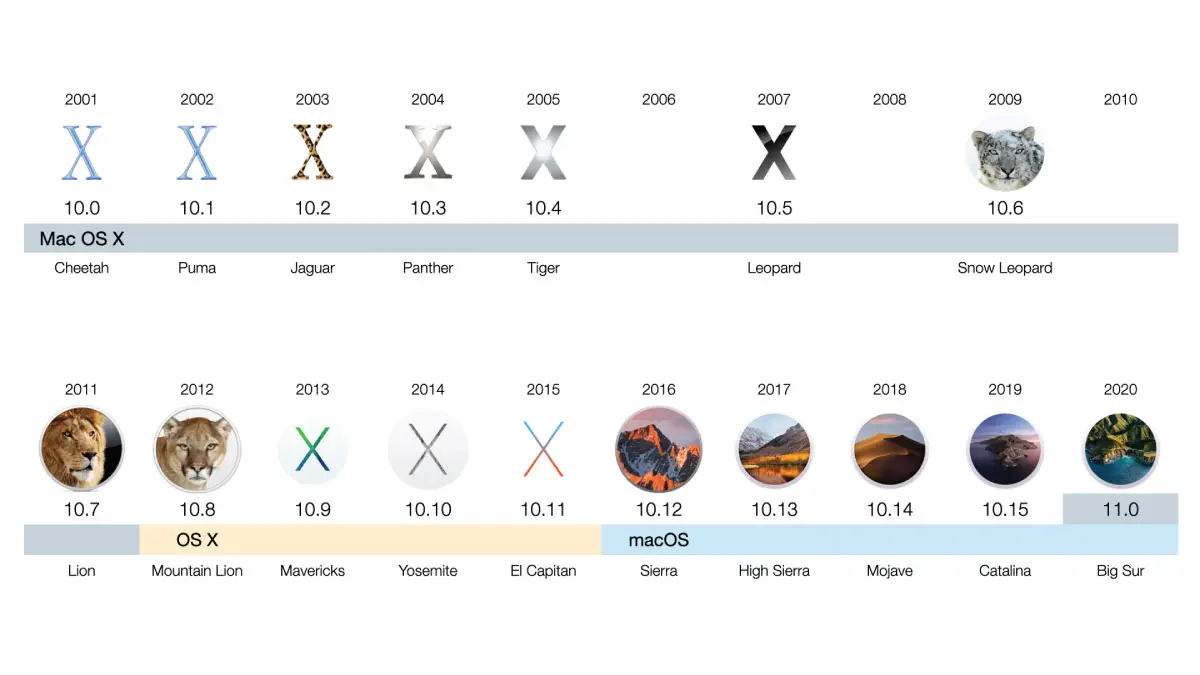

Apple's original Mac operating system debuted in 1984 with System 1.0, revolutionizing user interaction with a graphical interface and mouse. Through the '90s, Classic Mac OS evolved to System 7, Mac OS 8, and Mac OS 9, adding color UI and networking, but lacking features like protected memory. By 2001, macOS needed a reboot.

Apple responded with macOS X in 2001, built on a UNIX foundation and introduced alongside the Aqua interface. macOS X brought major advances: protected memory, multitasking, Safari, Spotlight, and Time Machine. The switch to Intel processors in 2006 and tools like Rosetta ensured legacy app support. Later updates such as macOS Snow Leopard and macOS Lion focused on performance and UI inspired by iOS.

In 2012, Apple rebranded to OS X, launching annual releases and deepening integration with iCloud and iOS. macOS Mavericks introduced power-saving features and free OS updates. Yosemite refreshed the UI, while El Capitan improved performance and security with System Integrity Protection.

With macOS Sierra in 2016, Apple aligned its OS branding across devices. New features included Siri on Mac, APFS, Dark Mode, and support for Mac Catalyst. In 2020, macOS 11 Big Sur delivered a bold visual overhaul and laid the foundation for Apple Silicon, using Rosetta 2 and Universal binaries to ease the transition.

Recent versions—macOS Ventura, Sonoma, and Sequoia—continue enhancing the platform. Ventura brought Stage Manager and Continuity Camera. Sonoma added widgets, Game Mode, and Safari Profiles. macOS Sequoia, announced in 2024, focuses on Apple Intelligence, delivering generative AI tools, iPhone mirroring, Genmoji, and deeper Siri integration. As Apple moves forward, macOS blends performance, privacy, and intelligent features in each release.

From the start, the Mac was defined by its GUI. Over the generations, macOS has continually refined the interface to balance visual appeal with usability. Early Classic Mac OS established principles like the menu bar, drag-and-drop, and universal clipboard. Mac OS X in 2001 introduced the iconic Aqua interface with its glossy candy-colored buttons and smooth animations, a leap forward from the pixelated classic UI. Over time, Apple evolved the look: OS X Yosemite (2014) brought a major redesign with flat icons, translucency, and a “flattened” modern aesthetic matching iOS’s style. In macOS Big Sur (2020), the interface was refreshed again with new squircle icons, a translucent menu bar, and a unified design language across macOS and iOS. macOS also gained system-wide Dark Mode in Mojave (2018) to reduce eye strain in low light. Today’s macOS combines sleek visuals with functional touches like Dynamic Desktop (wallpapers that change with time of day) and rich animations, keeping the experience fresh yet familiar for users.

A significant recent addition is Stage Manager, introduced in macOS Ventura. This feature provides an optional new way to organize windows on the desktop for improved focus. Stage Manager automatically arranges open apps into a tiled strip on the side, highlighting one active window in the center for distraction-free work. Users can group windows together into sets (e.g. all windows related to a project) and instantly switch contexts. Importantly, Stage Manager works in concert with existing windowing tools – Mission Control and Spaces remain available, and users can always reveal the desktop with a click. This coexistence underscores Apple’s iterative approach: instead of forcing one workflow, macOS accumulates multiple window management options (from classic overlapping windows, to Mission Control’s bird’s-eye view, to Stage Manager’s focused layout) to suit different user preferences.

Stage Manager, introduced in macOS Ventura (2022), exemplifies Apple’s ongoing GUI innovation. It automatically organizes open app windows into a sidebar, keeping the current window front-and-center for focus, while others remain readily accessible on the left. In the image, a Safari window is central and multiple apps are tiled on the side via Stage Manager, allowing quick context switching. This feature works alongside Mission Control and Spaces, reflecting how macOS layers new interface concepts on top of familiar ones rather than replacing them outright.

macOS has continually introduced features to improve everyday productivity and “it just works” usability. A hallmark example is Spotlight, the integrated search engine introduced in OS X 10.4 Tiger (2005). Spotlight lets users press Command+Space and instantly search files, documents, emails, contacts, web results and more. Over time it has grown smarter, providing rich results like definitions, unit conversions, and calculations directly in the search bar. Power users can perform advanced queries (e.g. using metadata like “kind:PDF date:this month” to narrow results) and navigate results via keyboard for lightning-fast information retrieval. Another beloved feature is Quick Look (debuted in OS X 10.5 Leopard), which allows pressing Space bar on any file to preview its contents in a glance – be it a PDF, image, or even video – without opening an app. This significantly speeds up workflows when browsing files. The Finder itself gained productivity boosts such as tabs (OS X Mavericks, 2013) to open multiple folder views in one window, and Tags for organizing files by keyword across folders. These often-underrated features help power users stay organized and efficient.

Mission Control, mentioned earlier, is a crucial tool for window management and multitasking. By swiping up on the trackpad or pressing a key, Mission Control presents all open windows in an organized overview, letting users quickly switch to any window or drag windows between virtual desktops. Paired with Spaces (multiple desktops), introduced in 2007’s Leopard and refined since, users can group windows by task or context on separate screens and easily swipe between them. Even before Stage Manager, Mission Control/Spaces provided a powerful way for heavy multitaskers to stay sane with many open apps. macOS also supports Split View (added in OS X El Capitan) to snap two apps into a half-screen side-by-side arrangement – useful for referencing one document while working in another, akin to Windows’ Snap feature.

Other built-in tools boost productivity and system mastery. Automator (introduced in 2005) allows users to create custom workflows and scripts to automate repetitive tasks without needing to code – e.g. renaming batches of files or extracting text from PDFs with drag-and-drop ease. In recent years, Apple has introduced the Shortcuts app (first on iOS, now on Mac in Monterey 2021) which brings an even more user-friendly automation interface, integrating with Siri and allowing complex multi-step routines (like resizing images, setting reminders, and emailing results) at the press of a button or voice command. Advanced users can also leverage the Terminal and shell scripting for automation, but Automator and Shortcuts make these powers accessible to anyone.

Security has been a strong focus of macOS, with Apple steadily layering new protections over time. Early Mac OS X was lauded for its Unix underpinnings, inheriting multi-user permissions, memory protection, and a robust networking stack from BSD, which already made it far more secure than classic Mac OS. In the 2000s, Apple added features like FileVault (introduced in OS X Panther 10.3) to encrypt users’ home directories, later upgraded to FileVault 2 in OS X Lion (2011) to provide full-disk XTS-AES encryption. Modern Macs ship with FileVault full-disk encryption available, keeping data safe even if a device is lost.

To protect users from malicious software, Apple introduced Gatekeeper in OS X Mountain Lion (2012) as mentioned. Gatekeeper ensures that only trusted apps can run on the Mac by verifying that apps are either from the Mac App Store or signed by identified developers (or else the user must explicitly override). This dramatically reduced malware incidents by adding a strong degree of user consent and code signing to app installs. Over the years, Apple has tightened Gatekeeper (for example, requiring apps to be notarized by Apple’s servers in modern macOS versions). macOS also employs sandboxing for apps (especially those from the App Store) – running apps in isolated containers with limited access to system resources and user data unless explicitly granted. This containment strategy, expanded around OS X Lion/Mountain Lion era, means even if an app is compromised, it cannot normally harm the rest of the system or access other app’s data without permission.

A major enhancement in OS security came with System Integrity Protection (SIP) in macOS 10.11 El Capitan (2015). SIP (also known as “rootless”) prevents even administrative/root users or processes from modifying critical system files and directories. Low-level system processes are further protected; for instance, third-party code cannot inject into system binaries, and kernel extensions require special permission. This makes it exceedingly difficult for malware or an attacker with escalated privileges to persist or tamper with macOS’s core. Complementing SIP, macOS includes a built-in Xprotect system (signature-based malware scanning for downloads) and runtime protections like ASLR and DEP at the system level.

In recent macOS releases, user privacy controls have been greatly enhanced in tandem with security. Starting with macOS Mojave (2018), Apple introduced a robust permission system (Transparency, Consent, and Control – TCC) that requires apps to get user approval before accessing sensitive data or peripherals – things like the microphone, camera, location, your Calendar/Contacts, or even personal files in Documents and Desktop folders. Visual indicators (e.g. an orange/green dot in the menu bar when mic or camera is in use) notify users when these devices are active, similar to iOS. Safari, the built-in browser, also leads in privacy with features like Intelligent Tracking Prevention to block cross-site trackers and fingerprinting defenses to hinder advertisers from identifying your device.

Importantly, Apple’s approach to features increasingly leverages on-device processing to preserve privacy. Much of macOS’s “smart” functionality – from Siri dictation to machine learning in apps (like Photos face recognition or Mail’s smart categorization) – is done locally on the Mac rather than sending data to cloud servers. Apple emphasizes that “what happens on your Mac, stays on your Mac.” As Apple states, they have integrated advanced on-device Apple Intelligence deep into macOS so it can be “aware” of your personal data without actually collecting it. For example, macOS’s typing suggestions, Spotlight suggestions, and facial recognition in Photos all happen with AI models running locally on Apple’s Neural Engine hardware, rather than uploading your data externally. This is only possible because Apple controls the whole stack, designing silicon (with dedicated ML cores) and software together to enable privacy-preserving computation. Even when cloud is needed for complex tasks, Apple employs techniques like Private Relay and Private Cloud Compute to anonymize or minimize data sent. This privacy-first philosophy sets macOS apart from some other platforms and aligns with Apple’s overall stance that privacy is a fundamental right, not a feature.

One of macOS’s biggest strengths is how well it works with other Apple devices like the iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, and even now Vision Pro. This ecosystem integration has grown considerably in the past decade. Under the banner of Continuity, Apple has introduced numerous features that make a user’s multiple devices feel like one cohesive experience:

Handoff: As part of OS X Yosemite’s Continuity features, Handoff lets you start a task on one device and seamlessly continue on another. You can begin writing an email or document on your iPhone, then sit down at your Mac and pick up exactly where you left off with a click – the Mac knows what you were doing on the phone and opens the corresponding app right to that content. Similarly, you can hand off websites between Safari on iOS and Mac, and so on. It’s all automatic using Bluetooth Low Energy to sense devices nearby.

Continuity Camera: This feature has two meanings: originally introduced in macOS Mojave (2018), Continuity Camera allowed users to snap a photo or scan a document using their iPhone and have it instantly appear on their Mac (e.g. inserting into a Pages document or Note). In macOS Ventura (2022), Continuity Camera was greatly expanded to let the iPhone serve as a high-quality wireless webcam for the Mac. With a simple mount, your Mac can automatically recognize a nearby iPhone and use its superior cameras for FaceTime, Zoom, etc. This unlocks capabilities like Center Stage (auto-framing you), Portrait mode (blurred background), Studio Light (lighting enhancement), and even an overhead Desk View using the Ultra-Wide lens to show your desktop during a call. These are things previously “never possible before with a webcam” that Continuity Camera achieves by leveraging iPhone hardware and Mac software together.

Universal Control: Introduced with macOS Monterey (2021) and iPadOS 15, Universal Control allows one Mac’s keyboard and trackpad/mouse to seamlessly control multiple nearby Apple devices. For example, set an iPad next to your Mac and simply move your cursor to the edge of the Mac screen – it will jump over to the iPad as if the iPad were an external display! You can then type on the iPad using your Mac’s keyboard, or even click and drag files between the two. All of this works automatically when devices are signed into the same Apple ID and near each other. It’s a powerful manifestation of Apple’s ecosystem advantage: enabling a Mac and iPad to act in concert without any special setup, as if they share one input system.

Handoff for Phone Calls and SMS: macOS can relay phone functionality from your iPhone. When your iPhone is on the same network, you can make or answer calls on your Mac (using the Mac’s microphone and speakers) – useful if your phone is charging in another room. Similarly, the Mac’s Messages app can send and receive not just iMessages but also regular SMS texts by routing through your iPhone, so all your messages appear unified on your computer. These Continuity features make the Mac an extension of your iPhone.

Handoff for FaceTime and Media: In macOS Ventura, Apple extended Handoff to FaceTime calls. You can start a FaceTime video call on your iPhone and then transfer it to your Mac with one click when you sit down, taking advantage of the Mac’s larger screen – and vice versa, you can move a call from Mac to iPhone if you need to go mobile. Additionally, features like AirPlay to Mac (introduced in macOS Monterey) let you use a Mac as an AirPlay target – for example, play a video or mirror your iPhone screen to your Mac’s display or use the Mac as a speaker. And with the Apple Watch, you can auto-unlock your Mac just by wearing your watch and sitting down (no password needed), as well as approve authentication prompts on the Mac via the watch (for things like viewing passwords or unlocking settings).

All these integrations – under names like Continuity, Handoff, AirDrop, etc. – create an ecosystem effect that is hard to replicate outside Apple’s world. A practical example: you can copy text or an image on your iPhone and immediately paste it on your Mac (Continuity Clipboard), or drag a file from your Mac and drop it onto an iPad app (with Universal Control). The devices intelligently sense each other and coordinate tasks so that a user can move between them fluidly throughout the day. For those deeply in the Apple ecosystem, these little conveniences are major productivity boosters and selling points for macOS.

Every version of macOS has also come with a suite of powerful built-in applications and features that enhance the user experience:

Safari: Apple’s web browser, first introduced in 2003 with OS X Panther, is the default on macOS. Safari is optimized for Apple hardware, often outperforming other browsers in efficiency and integrating features like iCloud Tabs (syncing open tabs across devices) and Reader Mode for distraction-free reading. Safari has also been a vehicle for privacy innovation (Intelligent Tracking Prevention, as discussed) and now supports Passkeys for passwordless login credentials. It remains one of the most energy-efficient browsers on Mac, contributing to longer battery life on laptops.

Time Machine: Introduced in Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard (2007), Time Machine provides effortless automatic backups of your Mac to an external drive or network drive. Its interface allows you to “step back in time” through hourly/daily snapshots of your files and restore entire folders or system state. The ease of use of Time Machine (just flip it on, and it handles versioned backups intelligently) has encouraged many more users to keep regular backups, an important part of security and data protection.

Mail, Calendar, Contacts, Notes, Reminders: The Mac has native apps for personal information management that sync via iCloud. Over the years these have gained features like Handoff support (e.g. composing an email on iPhone and continuing on Mac), natural language input (e.g. “Meet John for coffee tomorrow at 5pm” creates a calendar event), and collaboration (Notes allows shared notes with others, etc.). The Notes app in particular has evolved into a powerful tool with rich text, attachments, and recently (Sonoma) the ability to link notes to each other and view embedded PDFs in Notes.

iCloud and Continuity Services: macOS comes integrated with iCloud for not only file syncing (iCloud Drive) but also features like Photos (iCloud Photos library syncing pictures and providing Memories slideshows), Handoff as described, Universal Clipboard, Apple Pay (which on Mac uses a nearby iPhone or Apple Watch for Touch ID/Face ID authentication), and more. Even features like Sidecar (using an iPad as a secondary display for Mac) are built into macOS, extending the workspace for those with multiple Apple devices.

Media and Creativity Apps: Macs historically shipped with the iLife suite – iMovie, iPhoto (now Photos), GarageBand – empowering users to create movies, manage photos, and compose music out of the box. While these have evolved (Photos replaced iPhoto, etc.), a creative user can do a lot on a Mac without additional software. Apple’s pro apps (Final Cut Pro, Logic Pro, Xcode) are separate, but the inclusion of GarageBand and iMovie free is part of the Mac’s appeal for creators. The Music, TV, and Podcasts apps (since Catalina) handle media consumption seamlessly with the user’s purchases and subscriptions in Apple’s ecosystem.

Siri and Dictation: Since macOS Sierra (2016), Siri is built into the Mac, offering voice-controlled assistance – whether to set reminders, search the web, send messages, or adjust settings. Siri on Mac can also control system functions (“Increase brightness”) or find files (“Show me documents I worked on last week”). It operates with Apple’s privacy approach (random identifier, on-device processing when possible, etc.). macOS also supports robust dictation, leveraging the Neural Engine on Apple Silicon for near-real-time transcription of speech to text entirely offline (as of macOS Monterey’s enhanced dictation).

In summary, macOS’s core innovations span a wide range – from visually pleasing and intuitive interface designs to under-the-hood security frameworks and seamless multi-device experiences. This rich tapestry of features is what gives macOS its reputation for being powerful yet approachable. Apple’s tight integration of software and hardware allows macOS to run efficiently (e.g. Macs often stay fast for years, thanks to optimization like Metal graphics and now the Apple Silicon advantage) and to introduce features that leverage custom hardware (like the Neural Engine for ML tasks, Touch ID on MacBook Pros for quick login and sudo authentication, etc.). The result is an OS that caters to casual users with its simplicity, while providing tech enthusiasts and professionals plenty of depth to explore.

macOS has long been a platform beloved by developers, partly due to the rich set of developer tools and frameworks Apple provides. Central to this is Xcode, Apple’s official integrated development environment (IDE) for Mac (and all Apple OS) development. Xcode is a one-stop environment that includes a code editor, interface design tools, simulators, debuggers, and performance analyzers (Instruments). With Xcode and Apple’s SDKs, developers can create native apps in Objective-C or Swift that run across macOS, iOS, iPadOS, etc. Apple has continually improved Xcode to simplify development – for instance, Xcode’s Interface Builder allows drag-and-drop UI design, and since Xcode 11, it even includes a SwiftUI Preview canvas for live-coding UIs.

Swift, Apple’s modern programming language, was introduced at WWDC 2014 as a safer, faster alternative to Objective-C. By the time OS X Yosemite launched, Swift was made available for both iOS and OS X app development. Swift’s design emphasizes safety (by eliminating entire classes of bugs like pointer errors), speed (it’s compiled with high performance in mind), and interactive development with features like playgrounds. Over the past decade, Swift has become the primary language for Apple platform development and is open-source, with a large community outside of Apple as well. macOS fully supports Swift, and Apple even rebuilt many of its own frameworks to be Swift-friendly.

On the topic of frameworks: historically, macOS (from NeXTStep heritage) uses Cocoa, which includes AppKit as the UI framework for Mac apps. AppKit (written in Objective-C) provides all the standard Mac UI components (windows, buttons, menus, etc.) and has been the backbone of Mac app development for decades. Many of the macOS system apps are AppKit-based. However, as Apple’s ecosystem grew, they introduced UIKit for iOS (a similar framework tuned for touch interfaces) and more recently SwiftUI – a declarative UI framework that works across all Apple platforms. Unveiled in 2019, SwiftUI is a revolutionary framework that lets developers define their UI in a declarative Swift syntax and have it render on macOS, iOS, watchOS, and tvOS with (mostly) the same code. SwiftUI dramatically reduces the boilerplate for creating interfaces and provides live previews of the UI as code is changed. It also automatically adapts to things like Dark Mode, localization, right-to-left languages, and accessibility, saving developers a lot of effort. While SwiftUI is still maturing, it represents the future of UI development on the Mac, and Apple is clearly investing in it to eventually unify how apps are built across devices. That said, AppKit remains fully supported and necessary for certain Mac-specific behaviors (many Mac apps now combine SwiftUI for some parts of their UI with AppKit for others).

Another significant framework is Mac Catalyst (originally codenamed “Marzipan”). Introduced with macOS Catalina (10.15) in 2019, Catalyst allows developers to bring iPad apps to the Mac with minimal changes. In Xcode, a developer can check a box to enable their iPad app for Mac, and the system will automatically adapt UI elements like touch controls to work with mouse and keyboard. Under the hood, Catalyst is basically UIKit running on macOS, translated through a compatibility layer that bridges to AppKit. This was a strategic move by Apple to jump-start the Mac App Store with a larger variety of apps (since iPad has a huge app catalog). Many macOS apps (like Home, News, Stocks, Voice Memos) that shipped in Mojave/Catalina were actually Catalyst apps originating from iOS. For third-party developers, Catalyst offers a way to target Mac users without a completely separate codebase – the iPad and Mac versions of an app can share the same project and source code, with any Mac-specific tweaks handled conditionally. This cross-platform approach fits Apple’s theme of “write once, run anywhere in Apple’s ecosystem,” further strengthened by SwiftUI which was built to be cross-platform from the start.

Beyond UI frameworks, macOS shares many frameworks with iOS (especially since the move to 64-bit and Apple Silicon has brought the platforms even closer). Developers have powerful APIs at their disposal: Metal for graphics and GPU compute, Core ML for machine learning model integration (with the Neural Engine on Apple Silicon accelerating these), ARKit (augmented reality, though more relevant on devices with cameras like iPhone/iPad), Core Data for object persistence, CloudKit for syncing data via iCloud, and much more. And because macOS is a full Unix OS, developers also have access to lower-level POSIX APIs, scripting with shell or languages like Python (though macOS has been trimming some scripting runtimes in recent versions for security), and an X11 server if needed for porting Linux apps.

Apple provides extensive documentation and tooling for developers. With each WWDC (Apple’s developer conference), they release updated SDKs that take advantage of new OS features. For instance, when Apple introduced Apple Silicon, they provided tools to help port apps (like the Universal Binary Quick Start Program and letting developers use a Developer Transition Kit Mac mini with an A12Z chip to test their apps). They also ensured that frameworks like Metal and Core ML were optimized for the new hardware. The transition was smooth – developers could recompile apps as Universal 2 binaries that include both Intel and ARM code, and those who didn’t would still have their apps run via Rosetta 2 automatically.

To summarize, macOS offers a rich developer ecosystem with modern languages (Swift), powerful frameworks (AppKit, SwiftUI, Catalyst, and numerous core libraries), and top-notch tools (Xcode, Instruments). This environment encourages the creation of high-quality applications that feel at home on the Mac. It also means that many iOS developers can extend their apps to the Mac relatively easily, leading to a more vibrant software selection for users. As Apple’s platforms converge further (with iPads getting more desktop-like features and Macs gaining abilities to run iOS apps), we can expect development for macOS to become even more integrated with the broader Apple platform. Already, Apple’s goal is evident: a developer can build an app once and deploy it everywhere – on the phone, tablet, desktop, watch, and even the new Vision Pro – tailoring the UI with SwiftUI and sharing code across all. This is a compelling proposition and a key part of Apple’s strategy in attracting and retaining developers.

While macOS is designed to be easy for novices, it also contains a wealth of features for power users – those who want to tweak settings, streamline workflows, and get more done efficiently. Here are some notable capabilities and tips that advanced users often take advantage of:

Automator & Shortcuts: As mentioned earlier, Automator allows the creation of custom automation workflows using a simple drag-and-drop interface. You can build an Automator script to perform complex sequences (renaming files, extracting text, batch resizing images, etc.) and save it as a Quick Action or app. This can then be triggered from the Services menu or a keyboard shortcut. For example, you might make a service that takes any selected text and creates a new Note from it – available system-wide. Shortcuts, now on Mac (find it in Applications), brings many pre-built automation recipes and an easy way to script tasks that involve multiple apps. You can even trigger shortcuts with Siri voice commands or menu bar items. For the truly ambitious, Shortcuts on macOS can run shell scripts or AppleScript as part of a workflow, bridging the gap between GUI automation and code. Spending some time automating repetitive tasks can hugely boost productivity – essentially teaching your Mac to do the boring stuff for you.

Advanced Spotlight Searches: Spotlight isn’t just for typing a word and hitting Enter. You can use keywords and boolean operators to refine searches. For example, typing kind:pdf date:this month budget in Spotlight will search for PDF files containing “budget” modified within the last month. You can search by file kind (kind:images, kind:emails), by name (name:"report Q1"), by author (author:John for documents), and more. Additionally, in Finder’s search bar, clicking the “+” button lets you add criteria (like “File Size greater than 100MB” or “Photos taken after 2020”) – a GUI way to build complex queries. Another pro tip: in Spotlight results, pressing Cmd+Enter will open the containing folder of the selected item (to show you where the file lives), and pressing Space will Quick Look the result. Also, you can do quick calculations (e.g. type 527*12), currency conversions (100 USD to EUR), or define words (define: serendipity). Using Spotlight as a command launcher and calculator/navigator saves time compared to manually hunting through folders or opening Calculator app.

Mission Control & Window Management: For heavy multitaskers, mastering Mission Control and Spaces is key. You can assign apps to always open in a particular Desktop space (right-click the app’s dock icon > Options > Assign to Desktop X) – this way, you could have “Desktop 2” always for communication apps (Mail/Slack) and “Desktop 1” for coding or main work, etc. Swipe between desktops with a four-finger gesture. Within Mission Control, you can drag windows toward the top to create a new Space or merge them into full-screen Split View. Split View itself is invoked by clicking and holding the green window button, then choosing a side for that window; it will tile to half screen and let you pick another app for the other half. This is great for reference + writing workflows. Also, many people don’t realize you can drag windows to screen edges or corners to quickly resize them to half or quarter of the screen (though this is not as automatic as Windows snap, tools like Magnet can enhance it, but macOS does allow some edge-snapping). And of course, memorize useful window shortcuts: Cmd+` (backtick) cycles through windows of the same app, Cmd+Tab switches apps, and you can drag app icons in the Cmd+Tab switcher to other desktops. For those who want tiling window managers or more control, third-party apps exist, but macOS’s built-in tools are often sufficient once fully utilized.

Quick Look and Preview: Whenever you have to quickly inspect a file, Quick Look (Space bar) is your friend. But beyond just viewing, macOS’s Preview capabilities are deeply integrated. For instance, you can Quick Look an image or PDF and then hit the markup tool (pen icon) to annotate it right there – add signatures, text, shapes, crop or rotate images – then save, all without opening a heavy app. This is great for signing forms (Preview lets you create a signature via trackpad or camera scan, and store it for reuse) or making minor edits. The Preview app itself is extremely powerful: it can export files to different formats, combine PDFs (drag pages thumbnails between documents), adjust image color levels, and more. Many users never need a separate PDF editor because Preview covers the basics so well.

Finder Tips: In Finder, aside from tabs and tags, there are some neat tricks. You can press the space bar on a selected file for Quick Look, as mentioned, but you can also select a file and hit Cmd+I for a Get Info panel to see details and permissions (or Option+Cmd+I to get a single Info window that updates as you click different files). Renaming multiple files? Select them, then right-click > Rename X Items – macOS offers patterns to add text, replace text, or format (e.g. add sequence numbers). Also, Smart Folders in Finder can save a Spotlight query as a virtual folder – for example, a Smart Folder for “Photos from 2023” or “Documents tagged Important”. This automatically updates with files meeting the criteria, saving you from manually searching each time. Don’t forget Finder’s Path Bar (enable under View menu) which shows the file’s path and lets you drag-and-drop or Command-click components to jump to parent folders, which is a time-saver when organizing files.

Keyboard Shortcuts & Customization: macOS has a rich array of keyboard shortcuts, and you can create your own. In System Settings > Keyboard > Keyboard Shortcuts, a power user can add custom shortcuts for any menu item in any app (or across all apps). For example, if you frequently export to PDF in a particular app and it has a menu command, you could assign a custom hotkey to it. The same preference pane lets you enable goodies like Full Keyboard Access, which allows you to navigate dialogs and controls via keyboard (handy for those who prefer keys over mouse). Another tip: use Text Replacements (in Keyboard settings) to create shortcuts for phrases – e.g. typing “omw” can auto-correct to “On my way!” system-wide. Apple even lets you dictate emoji or special symbols through shortcuts if you enable it.

Terminal & Homebrew (for the truly advanced): macOS’s Unix core means all the power of a Linux-like terminal is at your disposal. The Terminal app (or third-party iTerm2) gives you access to zsh/bash and thousands of command-line tools. Tools like Homebrew (a popular package manager) can be installed to easily download and manage open-source software on the Mac, from development libraries to command-line utilities that Apple doesn’t include. For instance, you can use Homebrew to install programming languages, database servers, or utilities like wget. While not every Mac user needs to delve into the Terminal, for those who do, it opens up another world of efficiency – tasks like batch renaming files or finding text in files can often be done faster with one shell command than a series of GUI actions.

In summary, macOS provides layers of functionality – the surface layer is very simple (drag, drop, point, click), but beneath that, there are powerful tools waiting for users to discover. Many macOS power user tips involve chaining together built-in features: for example, using Automator to create a Quick Action that renames files, then assigning it a keyboard shortcut, so you can trigger it instantly on selected files. Or using a combination of Mission Control and Shortcut keys to jump between specific workspaces for ultimate window management zen. The OS is quite customizable in these ways, allowing each user to tailor their workflow. Exploring System Settings and the Utilities folder (which contains gems like Activity Monitor, Digital Color Meter, and the macOS Console for logs) can uncover many capabilities that turn a Mac from a basic appliance into a finely-tuned productivity machine.

Finally, Apple supports Accessibility features that power users can also leverage – for instance, Voice Control (you can control the Mac entirely with voice commands), Hot Corners (assign actions like Mission Control or desktop show to screen corners), and AppleScript for scriptable apps. There’s almost no limit to what you can make a Mac do with the right combination of features. Part of the joy for enthusiasts is discovering these tricks and making the Mac uniquely yours.

As we look forward, Apple’s trajectory with macOS is shaped by several key strategies and trends. One is the tighter integration of hardware and software – something Apple has always championed, but now taken to new heights with Apple Silicon. By designing its own Mac processors (M1, M2, and beyond), Apple can optimize macOS specifically for that silicon, enabling features and efficiencies impossible in the commodity x86 PC world. We already see benefits: Apple Silicon Macs have extraordinary performance-per-watt, allowing laptops to be fanless (MacBook Air) or have all-day battery life while still performing heavyweight tasks. On the software side, macOS can offload work to specialized chip components (the Neural Engine, media encoders, Secure Enclave) seamlessly. For example, macOS uses the Neural Engine for things like voice recognition and image processing acceleration. As Apple introduces new chip capabilities (say, a future enhancement of the Neural Engine, or dedicated AI cores), we can expect macOS to immediately leverage those. This vertical integration means the Mac platform will likely continue outpacing others in practical performance and unique features. It also means older Intel Macs will eventually be left behind as Apple optimizes new macOS versions exclusively for Apple Silicon and its unified memory architecture, neural net processing, etc. (Apple has already announced some macOS features that only work on Apple Silicon Macs, like certain intensive background effects in music or dictation).

Another pillar of Apple’s strategy is a privacy-first stance. We can expect macOS to continue expanding features that give users control over their data and minimize data leaving the device. In the era of cloud AI and big data, Apple is charting a different course by doing on-device AI. The latest macOS Sequoia’s emphasis on “Apple Intelligence” (which is essentially Apple’s AI/ML suite) explicitly promises that no one – not even Apple – can access your data when these AI features work. Apple achieves this through techniques like on-device processing and something they call Private Cloud Compute, where if the cloud is needed for heavy computation, only anonymized snippets of data are sent, and the servers are verifiably running code that protects privacy. Looking ahead, as AI in macOS grows (for instance, the ability to generate images or text via commands, as Sequoia introduced), Apple will likely differentiate by doing it in a privacy-respecting way. We might see an offline Siri that can answer complex queries using a large language model on-device, or image generation done with models running locally on the Neural Engine – thus no personal prompts or content ever leaves your Mac. This approach not only protects users but also aligns with Apple’s marketing – they can provide intelligent features without the “creepy” feeling of user data mining. In contrast to competitors who might integrate cloud-based AI assistants, Apple might lean on their hardware to deliver AI features that are both fast (low-latency, no internet needed) and private.

In terms of the Apple ecosystem, the future likely holds even more blurring of lines between devices. Apple has repeatedly stated they won’t merge macOS and iPadOS – believing that touch-based tablets and pointer-based computers serve different ergonomic needs. However, the distinction is less about capability now and more about form factor. With iPads getting more laptop-like (e.g. adding cursor support, pro apps like Final Cut, and M-series chips) and Macs gaining the ability to run iPad apps, we’re moving toward a unified application ecosystem. Apple’s introduction of technologies like Catalyst and SwiftUI is essentially preparing for a world where a user expects to use whichever device is convenient with the same apps and data. We may see unified app experiences where, for example, a creative app could seamlessly transition a workflow from Mac to iPad by just picking up an iPad and using Apple Pencil for a bit, then returning to the Mac – all with the same app continuity (perhaps leveraging iCloud for instant state sync). Some of this exists, but it can deepen.

Additionally, we have the emergence of Vision Pro (Apple’s AR/VR headset announced for 2024). Apple is introducing visionOS as a new platform, but importantly, visionOS can run iPad and iPhone apps out of the box, and presumably with developer tweaks, even Mac apps (especially if written in SwiftUI). In the long term, Apple likely envisions macOS being one facet of a broader computing experience that spans devices and even spatial computing. Imagine interacting with your Mac’s windows in augmented reality using Vision Pro – Apple demoed something along these lines where a Mac screen could be expanded into a giant virtual display viewed through the headset. This hints that macOS could extend into AR spaces, effectively escaping the physical screen. So the Mac experience might not be limited to the Mac’s hardware in the future but could be augmented by other devices in Apple’s lineup.

Another strategic angle is environmental sustainability and product longevity. Apple has set goals for carbon neutrality and reducing the environmental impact of its products. macOS plays a role here by enabling older hardware to stay useful longer through efficient software updates. For instance, Apple supported some Macs for 7+ years with OS updates, meaning users can keep using devices longer instead of replacing them (reducing e-waste). With Apple Silicon, Macs are so power-efficient that they use far less energy for the same tasks than previous generations, which at scale of millions of devices, contributes to energy savings. macOS also includes features like Optimized Battery Charging (which learns your schedule and charges the laptop battery to 80% until just before you need 100%, thereby prolonging battery health and device lifespan). Prolonging battery longevity means fewer battery replacements and less waste. Apple is also likely to continue emphasizing how their OS software is designed for durability – for example, features like Metal graphics and other optimizations ensure that even as software grows more advanced, the Mac can handle it without excessive performance loss over time. Apple often highlights that they make their products to last (and indeed many people keep Macs for a decade or more). Strategically, while Apple of course likes selling new hardware, they are balancing that with commitments to the environment – which include making hardware out of recycled materials and ensuring the software keeps them running efficiently. We might see macOS incorporate more power management features (beyond App Nap and power naps introduced in Mavericks) perhaps taking advantage of the efficient cores vs performance cores in Apple Silicon to minimize energy use for background tasks. This “silicon and software co-design” can wring out energy savings that others can’t easily match. For enterprise and eco-conscious customers, Apple’s narrative is that Macs are not just powerful but also green in operation (lower electricity usage, longer usable life, etc.).

Looking further ahead, a speculative but intriguing possibility is the role of AI and natural language in shaping how we interact with macOS. There’s a trend in tech toward conversational or AI-assisted interfaces. We see early hints: macOS has Siri and Dictation, and in Sequoia, features like ChatGPT integration were mentioned – presumably allowing AI-assisted writing and summarization system-wide. It’s plausible that in a few years, we might be able to ask our Mac to do things in natural language and have it execute complex sequences. Imagine saying, “Find all photos from last summer where I wore a red shirt and make a slideshow with music,” and the Mac does just that – using on-device ML to recognize images and automate an app workflow. Apple is certainly working on making Siri and Apple’s AI smarter (there are reports of internal large language model development). The key is they will do it in a uniquely Apple way: likely on-device to protect privacy, and tightly integrated with macOS’s apps and data (which is a big strength – Apple can integrate AI with your local photo library, mail, etc., without that data leaving your machine). We might see something like an “Apple GPT” directly in macOS in the coming versions, positioned as a helpful assistant for both everyday users and power users (imagine telling your Mac in plain English to organize your project files and it using Automator/Shortcuts behind the scenes to comply).

In terms of user experience, expect macOS to further blur the line between Mac and iPad in terms of features – macOS already borrowed Control Center from iOS (added in Big Sur to quickly toggle settings), and iPad borrowed the Mac’s Dock and multitasking concepts. Both OSes might continue to evolve in parallel, each inspiring the other. However, macOS will likely remain distinct in retaining the windowed interface and robust filesystem access that “truck” users (in Steve Jobs’s parlance) need. Apple will try to cater to both simplicity and complexity: e.g., the new System Settings app is iOS-like for casual users, but under the hood the advanced Terminal and file system are still there for those who need them. This two-layer approach might extend to more parts of the OS.

Finally, Apple’s strategy with macOS is undoubtedly to keep the Mac relevant in an increasingly mobile world. The introduction of Apple Silicon and constant stream of new features shows that Apple sees the Mac as a critical part of its ecosystem, not to be left behind in favor of only iPhones and iPads. In fact, Mac sales have been strong, and Apple often remarks that more than half of Mac buyers are new to the platform – indicating growth. To continue this, Apple will position macOS as the platform for creators and professionals, a message they reinforced by launching high-end hardware like new MacBook Pros and Mac Studio. They will emphasize things like the Mac’s advantage in creative software, development (coding) – Xcode only runs on Mac, after all – and now even gaming, which historically was a weak point. With Apple Silicon’s graphics and new developer tools like the Game Porting Toolkit (released in 2023 to help bring Windows games to Mac more easily), Apple is signaling that the Mac can compete as a gaming platform too. Sonoma’s Game Mode and forthcoming AAA game releases on Mac are part of that narrative.

In conclusion, the future of macOS looks to be one of a more capable, more connected, and more intelligent operating system – one that leverages Apple’s full control of hardware and software to deliver features in a way only Apple can. Whether it’s through deeper AI integration, seamless multi-device experiences, or continued refinements in performance and privacy, macOS is set to remain a cornerstone of Apple’s ecosystem. For users, this means the Mac will continue to be a reliable, forward-looking platform that marries the best of personal computing’s past (the productivity of a desktop OS) with the innovations of the present and future (mobile-inspired convenience, AI smarts, and beyond). As Apple likes to say, the Mac’s best days lie ahead, and from what we’ve seen with Apple Silicon and recent macOS updates, that certainly rings true. The journey from System 1 to macOS Sequoia has been remarkable, and it’s exciting to imagine what the next chapters will bring.

Enjoyed this comprehensive macos article? Follow our FaceBook page, Linkedin profile or Instagram account for more insights and practical tips on cutting-edge technology. Stay tuned with us for more insights, and join the conversation as we explore the technologies shaping tomorrow. Together, let’s embrace the future of tech in Singapore and beyond!

Reviewed and originally published by Esmond Service Centre on June 23, 2025

Mon to Fri : 10:00am - 7:00pm

Sat : 10:00am - 3:00pm

Closed on Sunday and PH